Why Do Establishment Intellectuals Ignore Slavery in Ancient Greece While Focusing on it in the American South?

They would ignore it in the South too if that were possible; here's why.

Chattel slavery, its serfdom variety, and its modern close cousin wage-slavery are seldom even mentioned, never mind highlighted and certainly not condemned in most accounts of European history (a.k.a. European 'civilization') from the days of ancient Greece and Athenian "democracy," to the present time. Instead we read of the doings and fightings and writings of the people who were NOT slaves or serfs or wage-slaves: the rich and powerful. The slaves and serfs and wage-slaves are always in the background, like the proverbial water that fish never see.

The way typical histories of European 'civilization' explain what happened at any given time is invariably by focusing on what the rich and powerful thought or did while--this is key!--ignoring the fact that the rich and powerful feared losing control over the slaves or serfs or wage-slaves and hence ignoring the fact that this fear is a huge factor in understanding what the rich and powerful did (read about this here), for example why they waged wars such as World War II as I discuss here.

The 'Wonderful' Athenian Statesman, Pericles

Here's the beginning of a typical article about ancient Greece's famous statesman and its famous Athenian 'democracy':

The so-called golden age of Athenian culture flourished under the leadership of Pericles (495-429 B.C.), a brilliant general, orator, patron of the arts and politician—”the first citizen” of democratic Athens, according to the historian Thucydides. Pericles transformed his city’s alliances into an empire and graced its Acropolis with the famous Parthenon. His policies and strategies also set the stage for the devastating Peloponnesian War, which would embroil all Greece in the decades following his death. [from https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-greece/pericles ]

Pericles is especially famous for his funeral oration, about which PBS writes:

In 431 [BC], shortly after the Peloponnesian War had broken out, Pericles delivered his famous Funeral Oration to commemorate those troops who had already fallen in battle. Recorded, and probably rewritten by the historian Thucydides, it is one of the primary sources on which our understanding of ancient Athens is based and provides a unique insight into just how Athenian democracy understood itself.

In the speech Pericles relates the special qualities of the Athenians, redefining many traditional Greek virtues in a radical new light.

The idea that the Athenians are able to put aside their petty wants and strive for the greater good of the city is a central theme of the speech. Bound together by bonds of mutual trust and a shared desire for freedom, the people of Athens submit to the laws and obey the public officials not because they have to, as in other cities, but because they want to. Athenians had thus achieved something quite unique - being both ruled and rulers at one and the same time. This had forged a unique type of citizen. Clever, tolerant, and open minded, Athenians were able to adapt to any situation and rise to any challenge. They had become the new ideal of the Greek world.

Pericles' view was obviously a very idealized one, and it ignored the realities of party factionalism, selfishness, and arrogance that were to soon manifest after his death.

As PBS notes, Pericles's view was an idealized one; but this idealized view is the one that dominates the image most people have of ancient Athenian democracy. Why is this? Well, one obvious reason is evident in PBS's last paragraph above, in which the list of negative things they say Pericles ignored does NOT include the proverbial elephant in the living room--slavery!

Pericles was the 'first citizen' of a slave society** (also see here and here.) According to the PBS commentary about ancient Athenian democracy, Pericles's words tell us truthfully how the ancient Athenians (meaning, of course, only the slave-owning ancient Athenians, since PBS is a 'fish that doesn't see the water') thought of themselves, and how we too ought to think of them after adjusting for the minor fact that, like all human beings, they were not saints and they engaged in some 'party factionalism, selfishness and arrogance.' PBS does not, however, mention the major negative fact--that the (slave-owning) Athenians enslaved other human beings!

Was Pericles a remarkable man? Yes indeed. I have copied below as a footnote* Pericles's famous funeral oration, and you can see that it is extremely eloquent. The slave-owners of ancient Athens were truly very lucky to have him as their leader, and they seem to have known it.

The Great and Wise Aristotle

About a century after Pericles's lifetime the famous ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, wrote:

That in a well-ordered state the citizens should have leisure and not have to provide for their daily wants is generally acknowledged, but there is a difficulty in seeing how this leisure is to be attained. The Thessalian Penestae have often risen against their masters, and the Helots in like manner against the Lacedaemonians, for whose misfortunes they are always lying in wait. Nothing, however, of this kind has as yet happened to the Cretans; the reason probably is that the neighboring cities, even when at war with one another, never form an alliance with rebellious serfs, rebellions not being for their interest, since they themselves have a dependent population. Whereas all the neighbors of the Lacedaemonians, whether Argives, Messenians, or Arcadians, were their enemies. In Thessaly, again, the original revolt of the slaves occurred because the Thessalians were still at war with the neighboring Achaeans, Perrhaebians, and Magnesians. Besides, if there were no other difficulty, the treatment or management of slaves is a troublesome affair; for, if not kept in hand, they are insolent, and think that they are as good as their masters, and, if harshly treated, they hate and conspire against them. Now it is clear that when these are the results the citizens of a state have not found out the secret of managing their subject population.

— Aristotle: The Complete Works by Aristotle

For Aristotle it is not at all controversial that there should be a select group of people, whom he calls 'citizens,' who should have leisure and not have to do any work (i.e, not have to provide for their daily wants) by having slaves involuntarily do the work for them. The only question is how this leisure is to be obtained, i.e., how to prevent the slaves from rising up against the citizens.

Like Pericles, there is an undisputed greatness about Aristotle: he used his leisure to devote his life to trying to understand the world by thinking rigorously about important philosophical questions, and wrote volumes about philosophy. But how many people today think of Aristotle as a representative of a slave-owner class? This elephant in the living room is virtually unseen and un-commented upon today. He is known simply as a great philosopher. (Ancient Roman society is likewise glorified and its basis in slavery minimized or covered up. Read a bit about how cruel and widespread this slavery was here.)

FAST FORWARD TO THE UNITED STATES ANTEBELLUM SOUTH SLAVE SOCIETY

With respect to the evil of slavery is there something about ancient Greece that deserves to be viewed with greater admiration than the slave society of the American South before the Civil War? In other words, is there a good reason for ignoring the slavery "elephant" in the ancient Greek "living room" while focusing on it--as virtually everybody does--in the antebellum American South's "living room"?

Some people might argue that a good reason for ignoring the slavery of ancient Greece but not that of the American antebellum South is that in the former there was no awareness that slavery was wrong but in the latter there was.

Yes, it is true that in the antebellum South, in contrast to ancient Greece, slavery was controversial, at least in the sense that although the slave owners thought it was not controversial many people in the United States were outspoken in declaring it wrong. Thus in ancient Greece, as far as I know at least, there was not an explicit abolitionist movement (which is not to say that the slaves supported their personal enslavement**, just that they may not have had a coherent theory about why nobody ever should be enslaved.)

But so what? What difference does it make that slave-owners in South Carolina knew that some people thought slavery was wrong but slave-owners in ancient Greece were not aware of any such belief (except, of course, by the slaves themselves**)? Consider the Aztecs who committed (or at least are widely believed to have committed—I’ve read some counter-claims) horrifying human sacrifices on a huge scale. I have never heard of anybody arguing that we should ignore this evil feature of Aztec civilization because the Aztecs didn't know that human sacrifice was wrong. So why should we give ancient Greeks a pass on their evil slavery?

Another (unpersuasive, in my view) argument that some give for ignoring the ancient Greek slavery "elephant" while focusing on the American South's is the claim that ancient Greece produced a rich culture--literature and art--while the American antebellum South did not.

But the antebellum slave South did produce a rich culture. I am not going to try to prove that the culture produced by the antebellum South was equal to or superior to that produced by ancient Greece, because that is not my point. My point is simply that if producing a rich culture were a valid reason for giving a society a pass on enslaving people (which I do not think it is), then the slave South (as I will discuss next) produced a sufficiently rich culture to justify getting a pass on its chattel slavery, and the fact that we do NOT give it a pass shows that the reason we give ancient Greece a pass is not because it produced a rich culture but for some other reason (which I will discuss below).

What Antebellum South Rich Culture?

I found an interesting source online called "The Library of Southern Literature: Antebellum Era." I suggest reading it. I read this about a person whose name I will tell you later:

...whose relationship to his southern heritage may indirectly be seen in his work. Although he was raised in Richmond, attended the University of Virginia, and edited the Southern Literary Messenger (1834-64) in Richmond from 1835 to 1837, he turned away from regional materials for the most part in his poetry, fiction, and criticism to devote himself to a form of literary expression that aspired to universality in style and structure. His poetry in which sound and sensuality superseded sense, his fiction in which meaning or message was secondary to emotional impact, and his criticism in which independently and objectively derived standards are used in the evaluation of artistic success, would help shape, first in Europe and then in this country, the modern literary sensibility. Creative writing throughout the world was never the same after...

Do you know who this is describing? It is Edgar Allen Poe.

I read this about the earlier period in the South:

For the first 50 years the southernmost outpost of the British empire in America, Charleston became a major commercial center and supported the development of a wealthy merchant and planter class, which in turn encouraged a lively cultural life including one of two newspapers published in the South, a library society, and bookstores. It was at one of these, Russell's Bookstore, that the members of the "Charleston School" gathered under the leadership of statesman and critic Hugh Swinton Legaré, editor and contributor to the Southern Review (1828-32). The group included among its membership romantic poet Paul Hamilton Hayne , editor of Russell's magazine (1857-60), and other lyrical sentimental poets of the pro-Confederacy school such as Henry Timrod, "Laureate of the Confederacy."

The most influential member of the group, and probably in his time the best-known southern writer, was William Gilmore Simms, editor during his career of 10 periodicals and author of over 80 volumes of history, poetry, criticism, biography, drama, essays, stories, and novels, including a series of nationally popular border romances about life on the frontier and historical romances about the American Revolution. He was one of the first to make a profession of writing. Simms's only serious rival as a writer in the South was Baltimore politician John Pendleton Kennedy, whose informal fictional sketches in Swallow Barn (1832) helped establish the plantation novel, which in its depiction of a mythic genteel past and an ideal social structure has found hundreds of imitators in American romance fiction.

The man often considered the greatest American fiction writer, Mark Twain, was a product of the slave south. The Library of Southern Literature writes:

Through studying Harris and the other southern humorists, Samuel Clemens, or Mark Twain, learned his trade, and his first published sketches, such as "Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog" (1865), belong to this school of humor. Born of southern parents in Missouri, and raised in the slaveholding community of Hannibal on the Mississippi River, employed as a steamboat pilot on the great river from St. Louis and Cairo down to New Orleans from 1857 to 1861, and enlisted briefly in the Confederate army before deserting to go with his brother to Nevada, Clemens and his formative experiences were more southern than western.

If producing the likes of Edgar Allen Poe and Mark Twain and artists in the medium of paint like the ones you can see here doesn't prevent us from condemning the antebellum South slave society as one not deserving of admiration, then why admire the slave society of ancient Greece just because it gave us some great statues and plays and philosophical writings?

Why Indeed?

Here's why ancient Greece (and ancient Rome for that matter also) gets a pass for its slavery from today's intellectuals, but the antebellum South does not.

Today's ruling billionaire plutocracy wants us to believe that class inequality based on wage-slavery (i.e., capitalism: read about this here), which is the modern form of chattel (and serf) slavery, is natural, hence totally non-controversial and rightfully ignored and rightfully never even talked about, and certainly not to be opposed. Today's ruling class wants class inequality to become as invisible as possible, to become the water that the fish doesn't see.

Because of the abolitionist movement in the United States and the fact that the Civil War was fought over the issue of slavery (yes it was, read about this here), however, chattel slavery in the United States is impossible to ignore; it is just too big and too recent an elephant! So, the ruling class was forced to do the next best thing: treat it as an historical fluke that came and went and has no significance for understanding the entire history of European 'civilization'*** or of the society we currently live in.

The ruling class does not want us even to know key facts about antebellum chattel slavery, such as 1) most southern whites hated the Confederacy (read about this here) and 2) chattel slavery was instituted for the purpose of enabling the rich upper class in the British American colonies to dominate and oppress ALL races of have-nots, whites as well as blacks, and NOT at all to benefit working class whites (read about this here.)

What the ruling class greatly fears is that we will see the elephant of class inequality (be it chattel, serf or wage slavery) as the key fact of ALL European civilization from at least the time of ancient Greece to the present. The ruling class fears that we will IDENTIFY not with the rich and powerful on whom all the history books focus but rather with the have-nots and their struggles** against the haves to make a more equal and democratic world. The rich fear that we will see that the real conflicts in the world have not mainly been between some rich and powerful haves against other rich and powerful haves but rather between the rich and powerful haves versus the have-nots (read about this here.) This is why the rich and powerful want us to admire Pericles's and Aristotle's ancient Greek slave society and why they praise it as the first "democracy."

The ruling class especially fears that YOU will do THIS!

------------------

* Here is Pericles's funeral oration:

Most of my predecessors in this place have commended him who made this speech part of the law, telling us that it is well that it should be delivered at the burial of those who fall in battle. For myself, I should have thought that the worth which had displayed itself in deeds would be sufficiently rewarded by honours also shown by deeds; such as you now see in this funeral prepared at the people’s cost. And I could have wished that the reputations of many brave men were not to be imperilled in the mouth of a single individual, to stand or fall according as he spoke well or ill. For it is hard to speak properly upon a subject where it is even difficult to convince your hearers that you are speaking the truth.

On the one hand, the friend who is familiar with every fact of the story may think that some point has not been set forth with that fullness which he wishes and knows it to deserve; on the other, he who is a stranger to the matter may be led by envy to suspect exaggeration if he hears anything above his own nature. For men can endure to hear others praised only so long as they can severally persuade themselves of their own ability to equal the actions recounted: when this point is passed, envy comes in and with it incredulity. However, since our ancestors have stamped this custom with their approval, it becomes my duty to obey the law and to try to satisfy your several wishes and opinions as best I may.

I shall begin with our ancestors: it is both just and proper that they should have the honour of the first mention on an occasion like the present. They dwelt in the country without break in the succession from generation to generation, and handed it down free to the present time by their valour. And if our more remote ancestors deserve praise, much more do our own fathers, who added to their inheritance the empire which we now possess, and spared no pains to be able to leave their acquisitions to us of the present generation.

Lastly, there are few parts of our dominions that have not been augmented by those of us here, who are still more or less in the vigour of life; while the mother country has been furnished by us with everything that can enable her to depend on her own resources whether for war or for peace. That part of our history which tells of the military achievements which gave us our several possessions, or of the ready valour with which either we or our fathers stemmed the tide of Hellenic or foreign aggression, is a theme too familiar to my hearers for me to dilate on, and I shall therefore pass it by.

But what was the road by which we reached our position, what the form of government under which our greatness grew, what the national habits out of which it sprang; these are questions which I may try to solve before I proceed to my panegyric upon these men; since I think this to be a subject upon which on the present occasion a speaker may properly dwell, and to which the whole assemblage, whether citizens or foreigners, may listen with advantage. Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighbouring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favours the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition.

The freedom which we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life. There, far from exercising a jealous surveillance over each other, we do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbour for doing what he likes, or even to indulge in those injurious looks which cannot fail to be offensive, although they inflict no positive penalty. But all this ease in our private relations does not make us lawless as citizens. Against this fear is our chief safeguard, teaching us to obey the magistrates and the laws, particularly such as regard the protection of the injured, whether they are actually on the statute book, or belong to that code which, although unwritten, yet cannot be broken without acknowledged disgrace. “Further, we provide plenty of means for the mind to refresh itself from business.

We celebrate games and sacrifices all the year round, and the elegance of our private establishments forms a daily source of pleasure and helps to banish the spleen; while the magnitude of our city draws the produce of the world into our harbour, so that to the Athenian the fruits of other countries are as familiar a luxury as those of his own.

If we turn to our military policy, there also we differ from our antagonists. We throw open our city to the world, and never by alien acts exclude foreigners from any opportunity of learning or observing, although the eyes of an enemy may occasionally profit by our liberality; trusting less in system and policy than to the native spirit of our citizens; while in education, where our rivals from their very cradles by a painful discipline seek after manliness, at Athens we live exactly as we please, and yet are just as ready to encounter every legitimate danger. In proof of this it may be noticed that the Lacedaemonians do not invade our country alone, but bring with them all their confederates; while we Athenians advance unsupported into the territory of a neighbour, and fighting upon a foreign soil usually vanquish with ease men who are defending their homes. Our united force was never yet encountered by any enemy, because we have at once to attend to our marine and to dispatch our citizens by land upon a hundred different services; so that, wherever they engage with some such fraction of our strength, a success against a detachment is magnified into a victory over the nation, and a defeat into a reverse suffered at the hands of our entire people.

And yet if with habits not of labour but of ease, and courage not of art but of nature, we are still willing to encounter danger, we have the double advantage of escaping the experience of hardships in anticipation and of facing them in the hour of need as fearlessly as those who are never free from them. Nor are these the only points in which our city is worthy of admiration.

We cultivate refinement without extravagance and knowledge without effeminacy; wealth we employ more for use than for show, and place the real disgrace of poverty not in owning to the fact but in declining the struggle against it. Our public men have, besides politics, their private affairs to attend to, and our ordinary citizens, though occupied with the pursuits of industry, are still fair judges of public matters; for, unlike any other nation, regarding him who takes no part in these duties not as unambitious but as useless, we Athenians are able to judge at all events if we cannot originate, and, instead of looking on discussion as a stumbling-block in the way of action, we think it an indispensable preliminary to any wise action at all.

Again, in our enterprises we present the singular spectacle of daring and deliberation, each carried to its highest point, and both united in the same persons; although usually decision is the fruit of ignorance, hesitation of reflection. But the palm of courage will surely be adjudged most justly to those, who best know the difference between hardship and pleasure and yet are never tempted to shrink from danger. In generosity we are equally singular, acquiring our friends by conferring, not by receiving, favours. Yet, of course, the doer of the favour is the firmer friend of the two, in order by continued kindness to keep the recipient in his debt; while the debtor feels less keenly from the very consciousness that the return he makes will be a payment, not a free gift.

And it is only the Athenians, who, fearless of consequences, confer their benefits not from calculations of expediency, but in the confidence of liberality. “In short, I say that as a city we are the school of Hellas, while I doubt if the world can produce a man who, where he has only himself to depend upon, is equal to so many emergencies, and graced by so happy a versatility, as the Athenian. And that this is no mere boast thrown out for the occasion, but plain matter of fact, the power of the state acquired by these habits proves. For Athens alone of her contemporaries is found when tested to be greater than her reputation, and alone gives no occasion to her assailants to blush at the antagonist by whom they have been worsted, or to her subjects to question her title by merit to rule.

Rather, the admiration of the present and succeeding ages will be ours, since we have not left our power without witness, but have shown it by mighty proofs; and far from needing a Homer for our panegyrist, or other of his craft whose verses might charm for the moment only for the impression which they gave to melt at the touch of fact, we have forced every sea and land to be the highway of our daring, and everywhere, whether for evil or for good, have left imperishable monuments behind us. Such is the Athens for which these men, in the assertion of their resolve not to lose her, nobly fought and died; and well may every one of their survivors be ready to suffer in her cause.

Indeed if I have dwelt at some length upon the character of our country, it has been to show that our stake in the struggle is not the same as theirs who have no such blessings to lose, and also that the panegyric of the men over whom I am now speaking might be by definite proofs established. That panegyric is now in a great measure complete; for the Athens that I have celebrated is only what the heroism of these and their like have made her, men whose fame, unlike that of most Hellenes, will be found to be only commensurate with their deserts. And if a test of worth be wanted, it is to be found in their closing scene, and this not only in cases in which it set the final seal upon their merit, but also in those in which it gave the first intimation of their having any.

For there is justice in the claim that steadfastness in his country’s battles should be as a cloak to cover a man’s other imperfections; since the good action has blotted out the bad, and his merit as a citizen more than outweighed his demerits as an individual. But none of these allowed either wealth with its prospect of future enjoyment to unnerve his spirit, or poverty with its hope of a day of freedom and riches to tempt him to shrink from danger. No, holding that vengeance upon their enemies was more to be desired than any personal blessings, and reckoning this to be the most glorious of hazards, they joyfully determined to accept the risk, to make sure of their vengeance, and to let their wishes wait; and while committing to hope the uncertainty of final success, in the business before them they thought fit to act boldly and trust in themselves.

Thus choosing to die resisting, rather than to live submitting, they fled only from dishonour, but met danger face to face, and after one brief moment, while at the summit of their fortune, escaped, not from their fear, but from their glory. “So died these men as became Athenians. You, their survivors, must determine to have as unfaltering a resolution in the field, though you may pray that it may have a happier issue. And not contented with ideas derived only from words of the advantages which are bound up with the defence of your country, though these would furnish a valuable text to a speaker even before an audience so alive to them as the present, you must yourselves realize the power of Athens, and feed your eyes upon her from day to day, till love of her fills your hearts; and then, when all her greatness shall break upon you, you must reflect that it was by courage, sense of duty, and a keen feeling of honour in action that men were enabled to win all this, and that no personal failure in an enterprise could make them consent to deprive their country of their valour, but they laid it at her feet as the most glorious contribution that they could offer.

For this offering of their lives made in common by them all they each of them individually received that renown which never grows old, and for a sepulchre, not so much that in which their bones have been deposited, but that noblest of shrines wherein their glory is laid up to be eternally remembered upon every occasion on which deed or story shall call for its commemoration. For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb; and in lands far from their own, where the column with its epitaph declares it, there is enshrined in every breast a record unwritten with no tablet to preserve it, except that of the heart. These take as your model and, judging happiness to be the fruit of freedom and freedom of valour, never decline the dangers of war. For it is not the miserable that would most justly be unsparing of their lives; these have nothing to hope for: it is rather they to whom continued life may bring reverses as yet unknown, and to whom a fall, if it came, would be most tremendous in its consequences.

And surely, to a man of spirit, the degradation of cowardice must be immeasurably more grievous than the unfelt death which strikes him in the midst of his strength and patriotism! “Comfort, therefore, not condolence, is what I have to offer to the parents of the dead who may be here. Numberless are the chances to which, as they know, the life of man is subject; but fortunate indeed are they who draw for their lot a death so glorious as that which has caused your mourning, and to whom life has been so exactly measured as to terminate in the happiness in which it has been passed.

Still I know that this is a hard saying, especially when those are in question of whom you will constantly be reminded by seeing in the homes of others blessings of which once you also boasted: for grief is felt not so much for the want of what we have never known, as for the loss of that to which we have been long accustomed. Yet you who are still of an age to beget children must bear up in the hope of having others in their stead; not only will they help you to forget those whom you have lost, but will be to the state at once a reinforcement and a security; for never can a fair or just policy be expected of the citizen who does not, like his fellows, bring to the decision the interests and apprehensions of a father. While those of you who have passed your prime must congratulate yourselves with the thought that the best part of your life was fortunate, and that the brief span that remains will be cheered by the fame of the departed.

For it is only the love of honour that never grows old; and honour it is, not gain, as some would have it, that rejoices the heart of age and helplessness. “Turning to the sons or brothers of the dead, I see an arduous struggle before you. When a man is gone, all are wont to praise him, and should your merit be ever so transcendent, you will still find it difficult not merely to overtake, but even to approach their renown. The living have envy to contend with, while those who are no longer in our path are honoured with a goodwill into which rivalry does not enter.

On the other hand, if I must say anything on the subject of female excellence to those of you who will now be in widowhood, it will be all comprised in this brief exhortation. Great will be your glory in not falling short of your natural character; and greatest will be hers who is least talked of among the men, whether for good or for bad. “My task is now finished. I have performed it to the best of my ability, and in word, at least, the requirements of the law are now satisfied. If deeds be in question, those who are here interred have received part of their honours already, and for the rest, their children will be brought up till manhood at the public expense: the state thus offers a valuable prize, as the garland of victory in this race of valour, for the reward both of those who have fallen and their survivors. And where the rewards for merit are greatest, there are found the best citizens.

And now that you have brought to a close your lamentations for your relatives, you may depart.

— The History of the Peloponnesian War: With linked Table of Contents by Thucydides

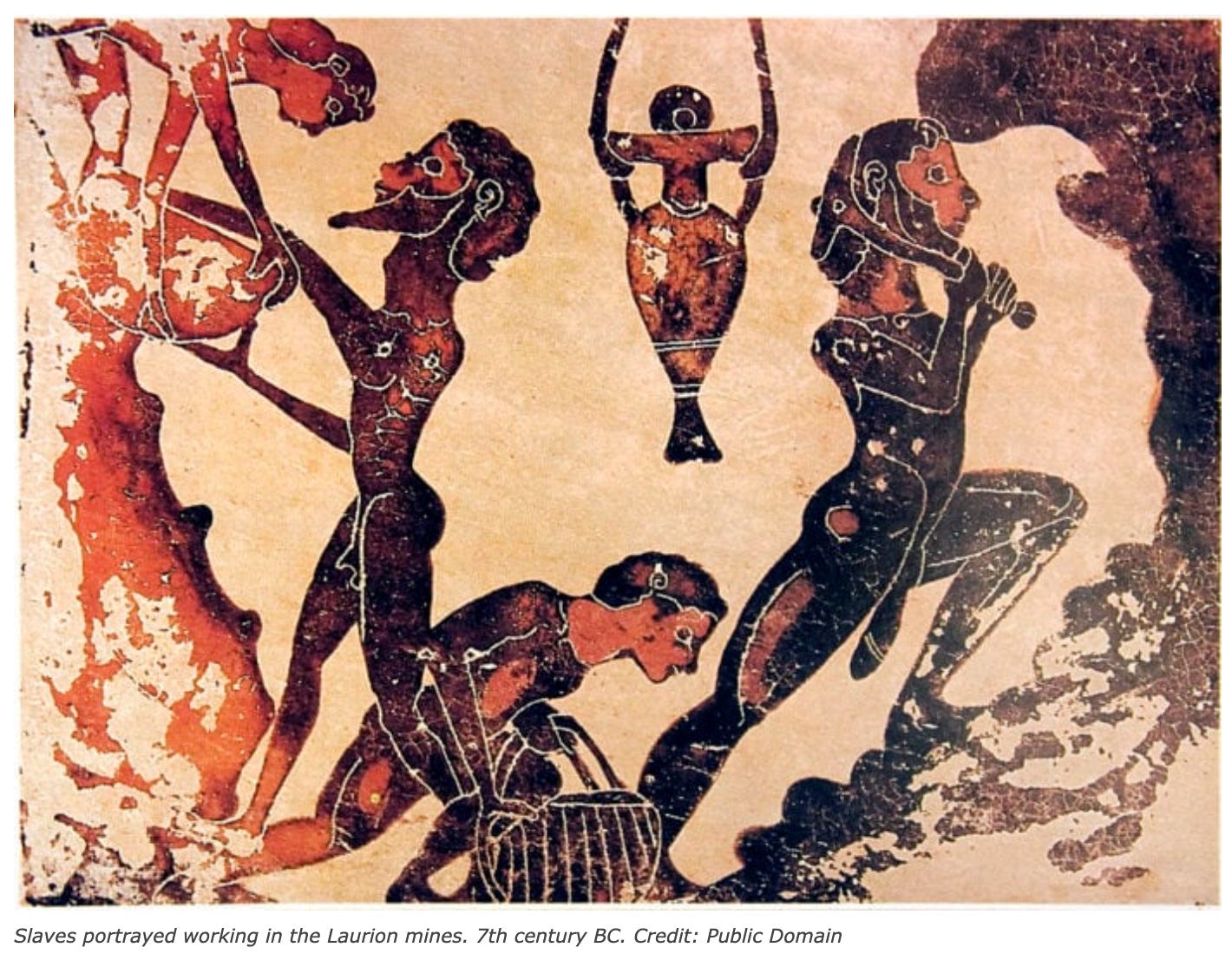

** "The worst positions for slaves were the jobs involving manual labor, especially in mines. As noted in the last chapter, one of the events that lost the Peloponnesian War for Athens was the fact that 20,000 of its publicly-owned slaves managed to revolt and escape from the horrendous conditions in the Athenian silver mines. Likewise, there was no worse fate than being a slave in a salt mine (one of the areas containing a natural underground salt deposit). Salt is corrosive to human tissue in large amounts, and exposure meant that a slave would die horribly over time. The historical evidence suggests that slaves in mines were routinely worked to death, not unlike the plantation slaves of Brazil and the Caribbean thousands of years later."

*** The struggles of serf-slaves against the rich and powerful, such as the Peasants Revolt of 1381 in England and The Great Peasants War of Germany, and the things the rich and powerful did to somehow defeat these struggles throughout European history are virtually unknown by most ordinary people today. Why? Because the "European history" we're taught treats such things as the properly ignorable background (the water invisible to the fish) to the (supposedly) actual important events: the deeds of the various rich and powerful people. When we're taught about wars between some rich and powerful people against other rich and powerful people, we're never taught that these wars were often for the purpose of controlling the have-nots (as you can read about here.)