Dear Fellow Anti-Establishment Political Activists

There are key questions we need to answer; we avoid answering them at our own peril.

Dear fellow anti-establishment political activists,

We’re all trying to persuade lots of other people to do something that we think will make a better world. And I think it is fair to say that none of us have yet persuaded as many people as we think are necessary to accomplish this. So it behooves us to figure out how come we haven’t succeeded yet. Towards that end, I strongly suggest that we address the following five key questions with explicit answers.

Question #1. What exactly do we mean by a “better world?” What would it take for us to say we have succeeded in making the better world that is our goal? Are we aiming for just a specific reform or set of reforms, or for a fundamental change in the structure of society?

People don’t get on a bus if they don’t know where it is going, or if they don’t want to go where it is going, or if they like its destination but don’t believe it can really ever get there, or if they like the destination somewhat but don’t think that it is worth the fare it costs to get there. So we’re not going to persuade people to “get on our bus” if we don’t tell them where it is going or if they don’t like where it is going, or if they don’t think it’s possible to get there or they don’t think it is worth the fare to get there, right?

What we are aiming for should make sense in light of the above. So what is it?

We need to tell people where “our bus is going” and that means we, ourselves, need to know this and express it clearly and unambiguously. Are we only aiming for what people dismiss as merely a band aid solution to a problem as big as cancer? Are we aiming for so huge a fundamental change that people dismiss it as impossible, like aiming to repeal the law of gravity? If not, then what exactly are we aiming for?

Question #2. Who exactly are the people we are trying to persuade to do something?

Is it everybody: rich, poor, nice, mean, citizen, non-citizen, any nationality or race or gender, etc.?

Is it only SOME people? If so, which ones?

Question #3. If we’re only aiming to persuade some people, are those people the vast majority or only a minority, possibly only a very tiny minority, of the population where we are active?

For example, regarding the number of people we might be trying to persuade to do something, there is a big difference between the vast majority of people who already today would love to remove the rich from power to have real, not fake, democracy with no rich and no poor and who therefore might be persuaded by us to do something to achieve that goal, versus the tiny number of people who already today would love to advance the permaculture driven regenerative economy and who therefore might be persuaded by us to do something to achieve that goal.

What can only be accomplished with the vast majority cannot be accomplished with merely a minority. Therefore if our goal requires the vast majority (which is what Question #4 is about) but we’re only aiming to persuade a minority, we can’t succeed, right?

Question #4. What is the main obstacle to achieving our stated goal? And what are additional important obstacles?

If the main obstacle is something we have no credible way of overcoming, then why are we advocating that people do this or that? If the main obstacle is something that we can overcome, then we need to explain what it is and why and how it can be overcome, in order to be persuasive, right?

We need to be brutally honest here with ourselves and those we are trying to persuade. If our goal is a modest reform (ending environmental pollution? advancing the permaculture regenerative economy?) but the obstacle is the ruling billionaire plutocracy—with its military/police force—that is opposed to even such a modest reform (for some reason, such as that it would cut into its profits or would weaken its social control), then we must admit this fact. Which leads to the next question.

Question #5. How exactly will the obstacle(s) to achieving our goal be overcome and our goal (a better world) be accomplished by people doing the X that we are trying to persuade them to do? The answer to this question should include a vision of exactly how lots of people doing X results in getting what we aim for, a realistic description that can be visualized showing how it actually might very likely happen. The answer to “How will we win what we say we want?” should be a truly believable scenario—in other words convincing.

In the 1960s in the United States, the obstacle to winning the modest merely reform goal of abolishing the racist Jim Crow laws was the powerful ruling class. The means of overcoming this obstacle—as you can read about in my “Why the Notorious Racist, LBJ, Made Sure the 1964 Civil Rights Act that Ended a Century of Jim Crow Segregation Laws Was Passed,” was building a Civil Rights Movement that was not merely reformist but implicitly, and imminently explicitly, revolutionary—a movement that made the ruling class fear that if it did not abolish Jim Crow it would be removed from power. And the only reason it was possible to build such a movement is because its goal was one that had the support of the vast majority (75% of whites and virtually all blacks) of the population. This is why our answer to Question # 3 is so important!

Note that it is not sufficient to argue that “Lots of people doing X is a good first step.” First steps don’t count for diddly squat unless there are follow up steps that get to the stated goal. It’s those follow up steps that we need to be describing explicitly, and persuasively arguing that they lead to the stated goal of a better world.

I remember when, during the Vietnam War, Allen Ginsberg persuaded lots of people to chant “Ommm” in front of the Pentagon because that would levitate the Pentagon and stop the war. Are we advocating something more sensible than chanting “Ommm,” more likely to accomplish the stated goal? I hope so. But if so, we need to explain clearly why it is so or else we won’t be persuasive.

Some things just “seem like a good idea” to some of us activists, but to the many people we’re trying to persuade to “get on our bus” they don’t seem like a good enough idea to elicit enthusiasm or energy not to mention sacrifice.

By answering this Question #5 we will discover either that a) there is a persuasive argument for why our stated goal can really be accomplished if all of the people whom we aim to persuade to do X do X, or b) it turns out we don’t actually have a persuasive argument for this and need to re-think what we’re asking people to do, and how we’re persuading them to do it.

For example, if we’re asking people to vote for somebody and our stated goal (see Question #1) is a fundamental change in the structure of society, can we make a persuasive argument that what we’re asking people to do will overcome the main obstacle to achieving the goal? Might our failure to persuade lots of people be due to a problem in this regard? A mis-match between the means we advocate and the end we want, a mis-match that many good people see clearly and for which reason they don’t do what we ask them to do?

Here’s how I address these five key questions

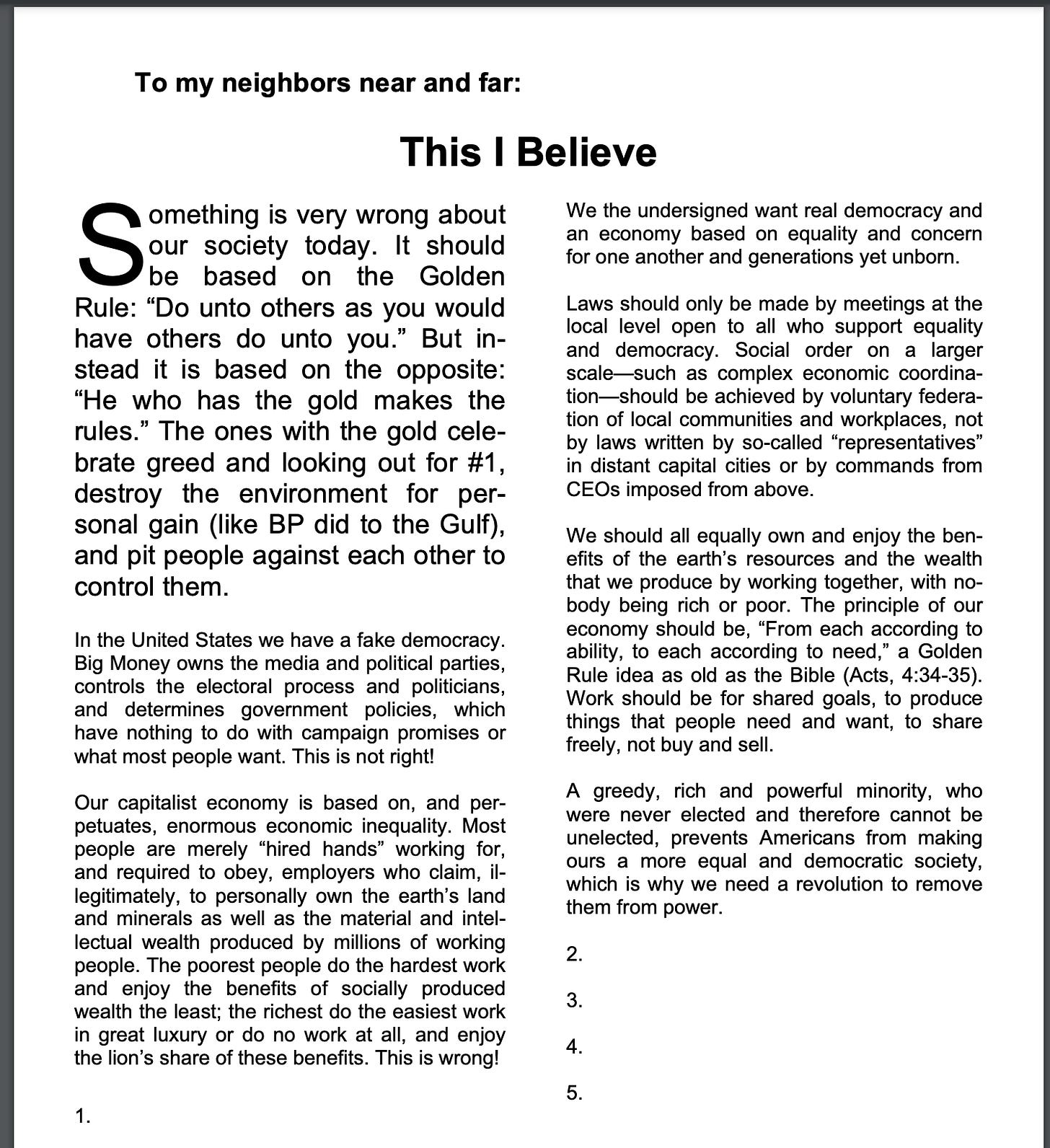

#1. The better world I aim for is egalitarianism, described here. It is NOT Utopia (as discussed here.)

#2. The people I aim to persuade are the people who already today share the egalitarian values of no-rich-and-no-poor equality, mutual aid and fairness and who already today would LOVE an egalitarian revolution to shape all of society by these values (even though most such people presently feel hopeless about the possibility of this ever happening.) I call such people egalitarians, even if they’ve never heard the word “egalitarian” before.

#3. Egalitarians are the vast majority of people in the United States, as shown here. They are the vast majority other nations as well. But not ALL people are egalitarians.

#4. The main obstacle to egalitarian revolution is that, while the vast majority of people would LOVE an egalitarian revolution, hardly anybody KNOWS that the vast majority would love an egalitarian revolution. Most people think that hardly anybody else wants an egalitarian revolution. Hence people feel hopeless about the possibility of egalitarian revolution, and that hopelessness paralyzes egalitarian revolutionary activism. An additional obstacle is the military/police force of the billionaire ruling class.

#5. The main obstacle (hopelessness due to feeling all alone in having an egalitarian revolutionary aspiration) can be overcome by various tactics (some of which are discussed here) to inform people and demonstrate to people that they are actually in the vast majority in wanting an egalitarian revolution. The other key obstacle (the military/police force of the billionaire ruling class) can be overcome by a massive egalitarian revolutionary movement in the manner described here.

In my REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT BUILDING 101 I provide answers to these five key questions and specific suggestions for acting on the basis of those answers. I am trying to persuade YOU to agree with me. Therefore, I would greatly appreciate hearing from you how YOU answer these five key questions, and if you disagree with my answers, please say why. This will make possible a very fruitful conversation!

Thank you.

John Spritzler

spritzler@comcast.net